I've been thinking a lot about personal data lately, the stuff that accrues as we live our lives in the presence of machines. About a year ago, I wrote down my thoughts on my own personal data: where it collects, what shape it takes, how it could be used.

The amount of data exhaust that we're all generating is pretty staggering. I'm fairly cautious about what I sign up for but I'm still finding more and more sources of data I can export and use. It's a bit of a bind, to be honest; I love having this data available to me but I don't love allowing companies to collect it ... What I am truly cautious about, though, is how much time I spend recording and collecting and transforming ... There is a whole bunch of toil baked into this hobby and I'm wary of creating an endless source of digital chores for myself ... I want to make it easy to collect as much of my own raw data as possible, even if I don't know exactly what I want to do with it right now.

Up until the end of last year, this curiosity was limited to me finding new sources of data, downloading them, and looking through these small windows into the past. What was the first thing I bought on Amazon (2004-12-7, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart Presents America, gift for a friend)? What was my longest bike ride recorded on Strava (2016-8-27, 118 miles from Seattle to Bellingham)? What was my first tweet (2008-3-27, "twit twit twit... nothing to say! :)")? It was fun and interesting and a nice distraction from what I was supposed to be doing on my laptop at the time, probably paying bills or reading another email from school.

Quick coffee stop in Coupeville, WA on the way to Bellingham.

Earlier this year, I started thinking more about just how much data I generate and what, if anything, this data could be used for in aggregate. The idea of being a "data-driven" human being, making decisions in the name of "optimization," is not appealing to me at all but there are a number of places where I would like to be able to combine data across services without allowing disparate companies to just vacuum it up wholesale.

- Could I combine daily notes in Obsidian (note taking app) with calendar entries and contacts to create a kind of personal CRM?

- Could I build a holistic view on athletic performance across the various trackers that I use (Strava, Oura, Garmin, and Apple Health) combined with notes I keep?

- What about a collection of data surrounding a date or event: texts sent, photos taken, financial transactions, and more to augment what I already remember and trigger memories I thought were lost?

- Is it possible to combine behavior (exercise, sleep and wake times, screen time, etc.) with mental state (anxiety, low mood, etc.) to find previously-unknown links between what I do and how I feel?

All of the things above could be stand-alone products on their own, and probably already exist in one form or another if I looked hard enough. But there are three big things that would stand in the way of me using something on the list above:

- Duplicating data from one another to another doubles the chance of that data leaking.

- I have to rely on whatever app I choose to give me exactly what I need or else I'll be tempted to pull the data out and work with it myself.

- If the app I'm using gets bought by a company I don't trust, shuts down, or just doesn't work for me anymore, I have no way of knowing that deleting my account deletes all the data they already have stored.

No matter how you cut it, trying to get all of your data into one service in order to pull insights out of it is problematic. Whether it's multiple apps working together or one single app that does everything, there is a fundamental problem with handing your personal data to a company and trusting them to both do the right thing and give you what you need, doubly so when you plug two apps together. For me, these issues prevent me from using a lot of different services that probably could be helpful.

The more I thought about it, the more important it felt to have as much of my data as possible immediately at my disposal. Maybe it's stored locally on my computer or in the cloud somewhere that won't be used without my consent, like an S3 bucket or a private git repo. Once it's downloaded, I could query it or transform it to another format or filter it and send the smaller payload to a specific app or service or even delete the data from the originating service. Not only that, I would have a backup of the original data always available in case I leave the service or it shuts down.

Data pipelines

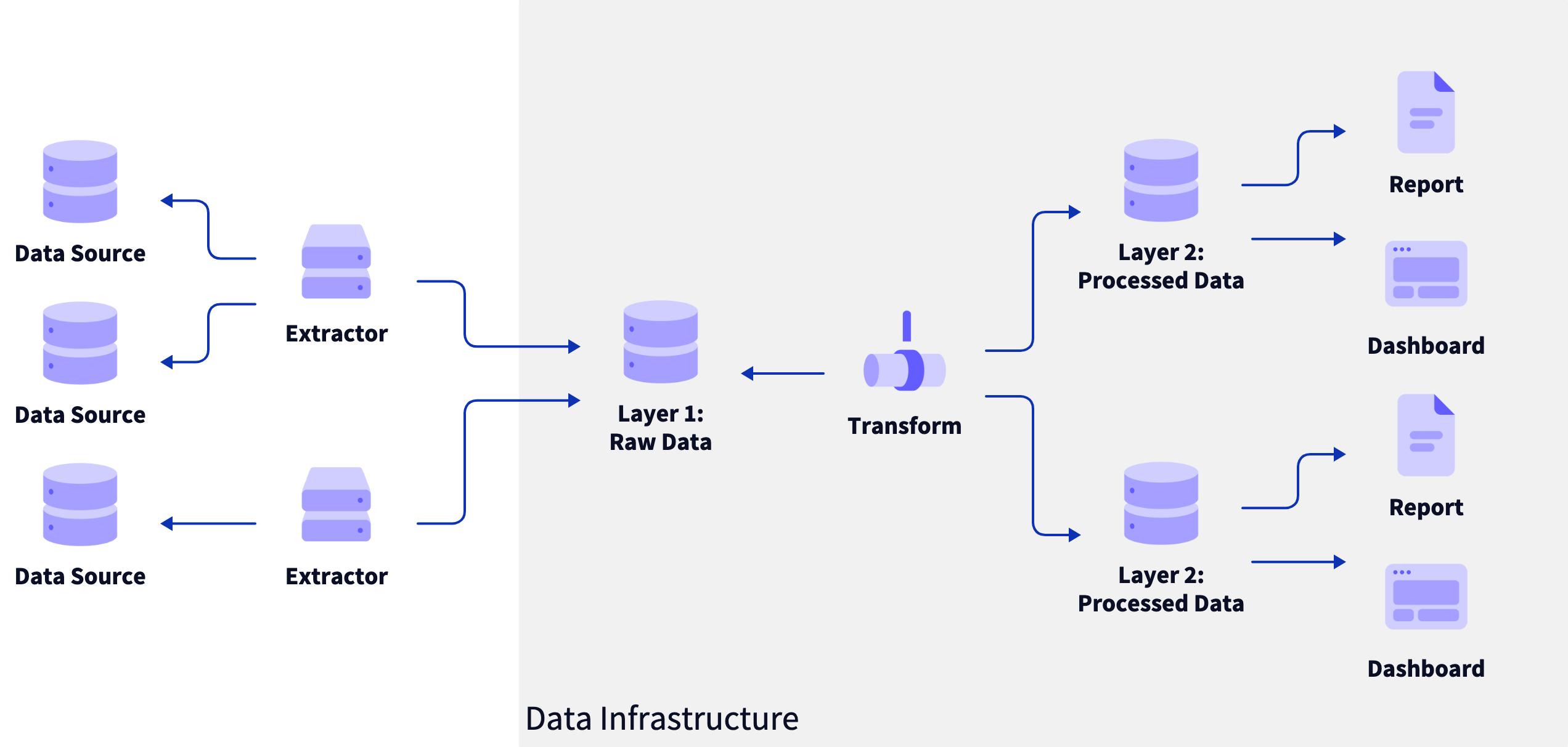

As I started to piece together this would work, it sounded more and more like the extract, load, transform (ELT) data pipelines I was using at work. For those unfamiliar with the concept, the basic idea is:

- You have a bunch of data stored in unconnected systems, some or all of which cannot be accessed directly. At work, this could be application databases containing customer-managed data, 3rd party systems like SalesForce, or something else.

- You set up a connector for each of the data sources you want to combine or examine to pull the raw data out and store it in a central location, often called a data lake. These connectors could be scripts, DBT, connection services like FiveTran, pre-built integrations, or any number of things.

- Once the raw data is in the central database, transformations can be run at whatever interval with results stored in tables that can be dropped and recreated during each run. These could be filters, combinations, calculations, or something else.

- Analytics, reports, and other tools can now operate on transformed data, making it easier to reuse logic.

Putting this all together looks, conceptually, something like this oversimplified but still somewhat complicated diagram:

Applying this system to any one of the personal data combinations I listed above seems to be a good fit:

- Use services that store their data in a way that you can't directly query.

- Extract that data into a central repository you control, like locally on your machine.

- Make connections, combinations, calculations, and more without hitting rate limits, dealing with pagination, or waiting for requests to complete.

- End up with text files or CSVs or metrics or anything else you need, ready to review, publish, or share with others.

I want to pause for a moment and recognize that this particular idea is not original to me. I've been thinking about how to backup and use personal data for a few years and have, recently, been picking up ideas from various tools and blog posts I've found out there: the idea of a human programming interface (HPI); a personal data search engine; outboard memory using a memex. This is just scratching the surface but I wanted to give credit where credit is very much due.

The main idea here is that we can apply some modern data infrastructure ideas to the world of personal data and, potentially, end up with a sustainable system for collecting, backing up, transforming, and querying data across multiple platforms. This puts your data in your control and reduces your reliance on companies to do the right thing on your behalf.

The system

As I started to imagine what this might look like as a complete system, I realized that what I didn't want was a complicated software system that I needed to maintain by myself for the rest of my life. There is definitely a bit of compulsion behind this type of data hoarding and missing out on a sunny day at the park because I have to fix a bug with my data pipeline is not what I want my life to become. Whether this was a community of like-minded people or some kind of open-core business, I want to build something that others are able to contribute to and extend for their purposes.

To that end, I came up with a list of attributes, or values, that need to guide the creation of whatever this might become beyond Just Another Repo. I see these as table stakes, not aspirational recommendations:

- File over app: Storing data in discreet, human-readable files is critical for portability and long-term durability.

- Local first, cloud optional: Pulling all of your data out into Yet Another Service defeats the point but access across devices and networks is a valid use case.

- Privacy by design: This system should be trustworthy based on how it's designed and built, not just because I say that it is.

- Open source and bring your own (BYO) components: Everyone has a different level of trust so I want this system to be 100% deployable, usable, and auditable on its own.

- Make it as easy as possible: I want this all to be as easy to setup and run as possible, making the barrier to entry much lower than "you need to be able to write code."

- Durable formats and architecture: The data at rest should be human-readable and easy to parse, regardless of how it started. The system itself should "just work" for as long as possible.

I spent some time writing and diagramming and I think I have, if not the answer, then at least a step in the right direction.

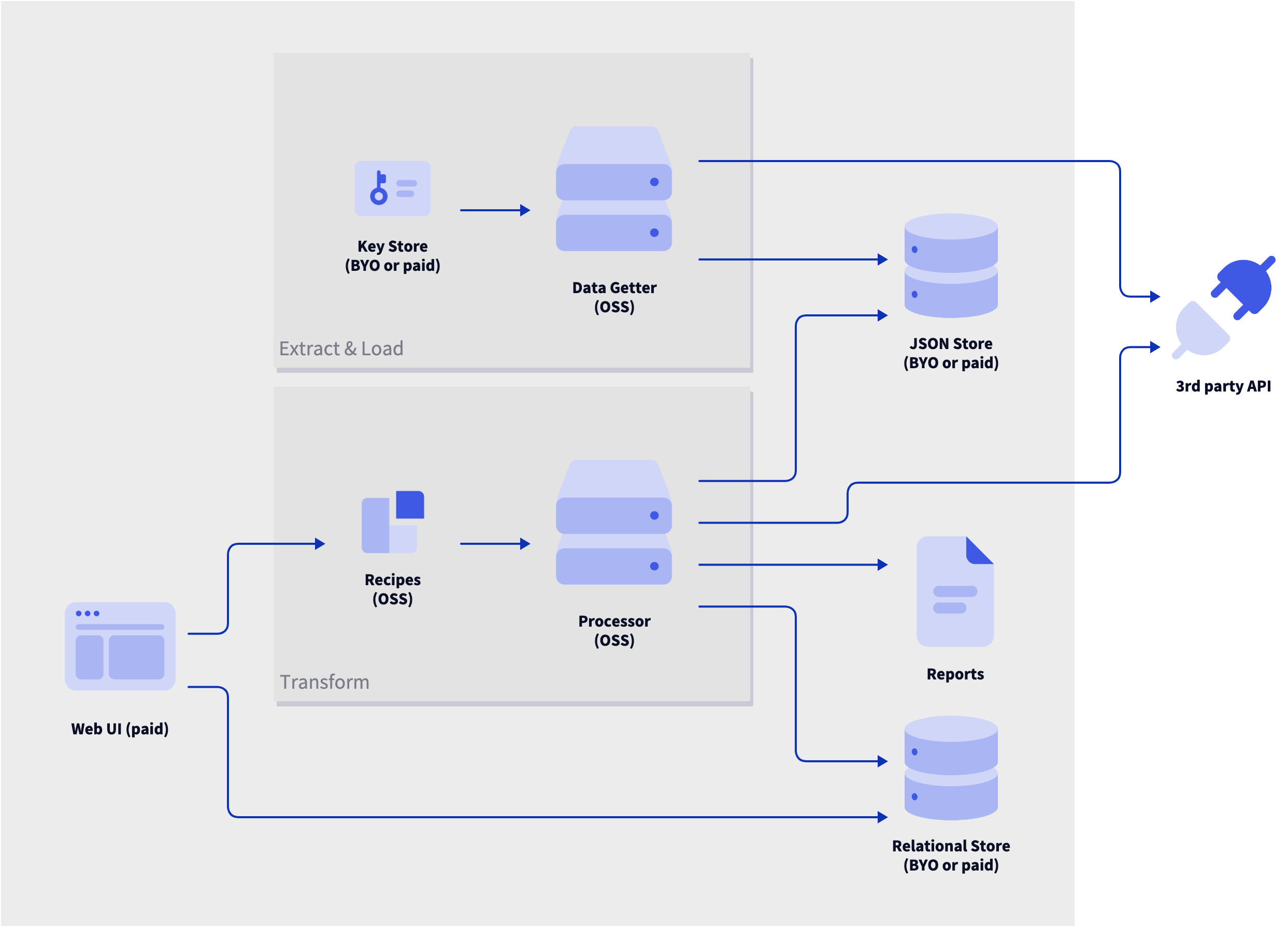

Each of the components are described below, in terms of their job(s) to be done. I use these terms throughout the rest of the post.

- Data Getter: This service gets data from APIs and imports data from export files, both provided by the services themselves. It needs to be called frequently to pull in the latest data and be able to iterate through paginated endpoints to download all historic data. It needs to be cautious about rate limits, provide good reporting, and be able to recover from errors so it can run generally unattended. This component is open source so it can be audited by users for key management, API contracts, and data handling.

- Key Store: This component stores the credentials needed to call APIs and can be either user-controlled or provided as a part of some future paid service. The keys are provided for each API run, allowing for key rotation and separation of concerns.

- JSON Store: This component receives plain JSON files from the Data getter and makes it available to the Processor. This could be the file system on the machine that is running the data getter or a cloud storage service like AWS S3, Google Drive, or similar. Like the Key store, this can be provided by the user or some future paid service.

- Processor: This service runs against the data in the JSON store but is decoupled from the data getting schedule; in other words, this service does not need any communication with or knowledge of the Data getter. The interface here could be anything - declarative JSON or YAML, "low-code" development environment, domain-specific language - and the output could be anything as well. The idea here is you have logic of some kind that transforms the source data into new data in whatever format or actions against the source API or other APIs. You could run this in the cloud if your input and output are all there as well or you could run it locally to save transformed data on your machine (as, say, Obsidian notes).

- Reports: Represents the idea of transformed data in the desired format.

- Recipes: As you work with your data from the services that you use, you will begin to collect information on the format, structure, and content of that data. This information is in the shape of the transformations used by the Processor and can be published to a public repository of some kind that others can pull down and use as well. The idea here is that, instead of maintaining a massive universal schema of all the APIs in the world, there is a collection of transformations you can experiment with, modify, and republish, a bit like using and forking a Git repo. You can try recipes against your own data as a "dry run" and adopt them if everything works as expected.

- Relational Store: This is partly calling out another output possibility for the Processor but it's also an important part of that future paid service I keep referencing. Transformed data could be pushed to a database owned by the user or provided by the paid, open core service. This could be configured with whatever access is necessary, providing a way for additional services to get access to your custom-filtered personal data.

- Web UI: This would likely be a closed-source part of the paid service, providing an easy way to monitor the system, create recipes, and access transformed data. This would not change the functionality of the rest of the system, rather it would help bridge the technical gap and provide a simple interface for anyone unwilling or unable to create their own processing and reporting logic.

If it's not clear in the descriptions above, a critical attribute of this system is that all the different parts can be self-hosted and maintained for free. If you are critical of giving a 3rd party service access to your credentials and data (as I am), then you can spin all of this up on your own hardware and the whole thing should work as described. Everything here is designed to be both modular and extensible, making the system work for many levels of paranoia and technical ability. The "paid service" I keep referencing is just a theoretical way to support work on this project in some distant future. Always the pragmatist.

What might not be completely clear in the diagram above is where the different layers of data end up. Because this system is meant to be flexible and extensible, I don't think there needs to be system-level opinion of how that comes together. In a data pipeline for a software company, you need to be clear and deliberate about where and how sensitive data is stored. If you're just pulling down your own data and creating new connections and combinations, this is not as big of a problem. Your layers could be any of the following:

- Pre-processing step to combine and filter raw data into new JSON files in the JSON store or Relational store

- Descriptions of "models" like

PersonorLocationthat indicate data sources and linking - A separate instance of the Processor running specific recipes to create foundational data

- No layers at all, just pipe raw data to your outputs

In use

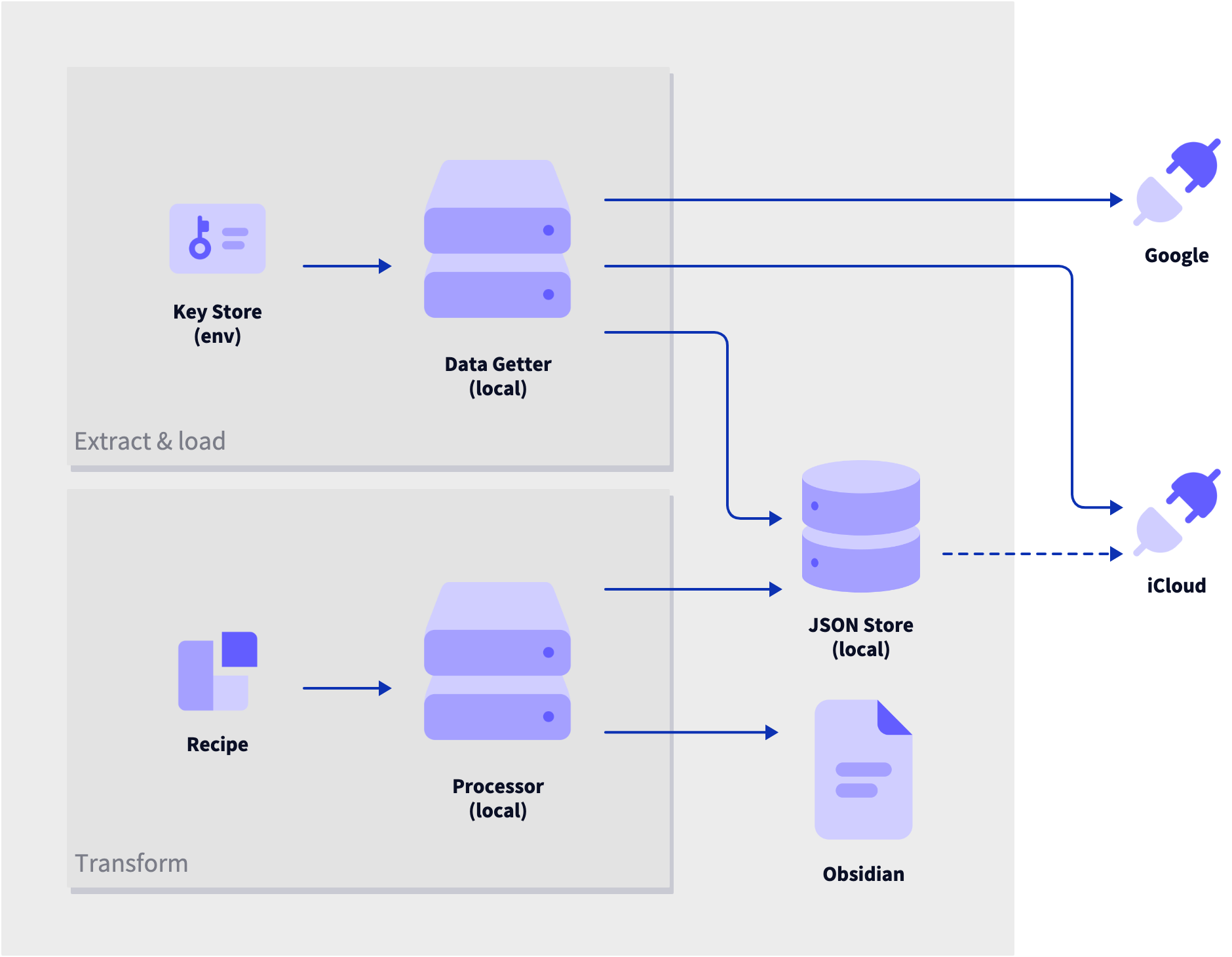

So, let's take the first idea listed above, a personal CRM, and see if we can build it, conceptually, using the system above. This is a system that's specific to my work flows and includes both stored cloud data and a local system.

Here's what I'm using currently and how I want it all to fit together:

- Input Events are stored in Google Calendar

- Input: Contact data is stored in iCloud

- Transform: Contacts are linked to events with email

- Transform: Contacts are linked to notes by full name

- Transform: Events are linked to notes by dates in

YYYY-MM-DDformat - Output: Notes about people and dates are stored in Obsidian

Since the output is a local file, the processor, at least, will need to be local. To keep things simple, the rest of the components will be local as well. This will, incidentally, allow the retrieved raw JSON to be backed up in iCloud just by virtue of being saved to the right directory. Full circle!

What we're describing here looks like this:

With the Data Getter running, what we'll have waiting for us is a collection of events in this (filtered) format:

{

"summary": "A fun event!",

"start": {

"date": "2024-05-16",

// ...

},

"end": {

"date": "2024-05-16",

// ...

},

"attendees": [

{

"email": "josh@joshcanhelp.com",

// ...

},

{

"email": "bob@bobcanhelp.com",

// ...

}

],

// ...

}... and a collection of iCloud contacts looking like this:

{

"firstName": "Josh",

"lastName": "CanHelp",

"emailAddresses": [

{

"field": "josh@joshcanhelp.com",

// ...

},

],

// ...

}We'll connect the event to the contact using the email address and output a line in the daily note for that date.

Note: I'm skipping over the details of the Data Getter because, in the end, that service is meant to "just work."

For those of you out there who can write code, this is not a terribly involved task. Parse the JSON, get all the email addresses, find them in the iCloud data, grab the names, find the daily note files, and print it all out. This is ... fine and much easier to do once you've got all the data you need sitting nearby. But the idea of these Recipes is to:

- abstract this work so the same code can operate in multiple contexts

- allow transformations to be shared with other people to be used as-is or as a base for new ones

- combine recipes for the same data source to create a loose schema that can inform data shape and types without maintaining strict definitions

- allow creation via plain text editing or GUI at some point in the future

All of this, in my mind, points to some kind of declarative way to describe the data sources, their relationships, and the output that we want. The Processor would run a number of pre-flight checks against the stored data to make sure that the input sources exist, that the output destination is configured, and a map of how we get from input data to output.

Let's try to write a Recipe that represents all this in a way that makes sense for what we're trying to accomplish. Note that this is all just conceptual at the moment and the choice to use YAML is insignificant at this stage. Starting with the input data:

input:

google:

calendar:

summary: 'event_summary'

start.date: 'start_date'

start.time: 'start_time'

'attendees[].email': 'event_emails'

icloud:

contacts:

firstName: 'first_name'

lastName: 'last_name'

'emailAddresses[].field': 'contact_emails'

# ... more to come ...Here, we're telling the Processor that we have two data sources, google and icloud, which can be checked against either existing data files or some configuration to figure out if we expect those sources to exist. Then, each of the sources have one set of data, which would be validated directly on the data that we either have locally or are connected to. Finally, we indicate the fields that we're using and a shorthand name to be used later in the pipeline. Our pre-check can make sure that those names are unique across all sources but, because we're not processing the data yet, whether the fields exist or not is handled later. Note that anything with a [] in it tells us that we're handling multiple values.

Next, we're going to tell the Processor what output we want and what it's shape should be. The possibilities for output is effectively infinite but, just like with the rest of this, I want to start with capable default functionality and allow for lots of places to hook into the process. Standard functionality could just be simple file system operations like writing to a CSV or appending to a text file or making another JSON file.

This should cover a number of use cases but, like the Data Getter, I want to also include user-contributed modules for specific services and tools. Each contributed output would have configuration of some kind that would be checked (file paths, API credentials, etc.) and allow folks to define specific templates, output locations, and metadata to use.

For our CRM use case, this could look something like:

inputs:

# ...

output:

file:

- strategy: 'csv'

data:

path: '/Users/user/Downloads/'

fields:

- date

- start_time

- event_summary

- location

- event_emails

obsidian:

- strategy: 'daily_notes_append'

data:

date: 'date'

template: |

- ${event_summary} with ${:loop:contact_emails:, :[[${first_name} ${last_name}]]} at ${start_time}

# ... more to come ...In the example above, we're using a theoretical Obsidian-specific module that provides capability for working with daily notes. When being called from a recipe like this, it would check for necessary configuration (in this case we would need a path to the local files at least) and fail if it didn't have the information it needed. Once it passes pre-flight, the module would tell the Processor how to find the daily note for the data being provided and what to do with the data once the file is found or created.

The last, and most important piece, is defining how the data should be modified and connected. In keeping with our "pipeline" concept, we'll define a set of actions to be taken on the data that we have:

inputs:

# ...

outputs:

# ...

pipeline:

- field: 'start_date'

toField: 'date'

- field: 'start_date_time'

transform:

- 'toStandardDate'

toFieldUpdateIfEmpty: 'date'

- field: 'start_date_time'

transform:

- 'toStandardTime'

toField: 'start_time'

- field: 'event_summary'

transform:

- 'trim'

- field: 'event_emails'

linkTo: 'contact_emails'Walking through this step-by-step:

state_date, which was defined in theinputs, should be converted to the standard date format ofYYYY-MM-DD. Thetransformationsarray points to built-in and extended functions for processing these fields.event_summaryshould have surrounding whitespace removed and case normalized.- iCloud contacts are related to Google events when the email address for a contact is found in the event attendees list,

event_emails. We're saying that one source can be combined with the other and used in the same context. If we had another source that also used an email address as an index, we could just add anotherpipelineentry and expand the data accordingly. - The daily note date should come from the

start_date, which was converted above.

Another note about data layers here ... The Data Getter is saving raw JSON parsed out into days but, after that, we just have what we have. But, for so many things that we want to do, we're going to be filtering, augmenting, connecting, and transforming this data into what we want. In many cases, the processing that's required for one output will be the same as others and duplicating transformations and links would be "fork bomb," as a friend described it. To help with that, we could define a set of "pre-processing" recipes that builds new JSON files from our data sources, creating a new source that can be truncated and replaced for each run of the Processor. This would simplify the recipes and provide smaller datasets to work with.

Assuming everything was wired up correctly, running this recipe would output the following block on all daily notes that had events from Google:

**Google Calendar events**

- Doctor appointment at 2:00 PM

- Partner introduction with [[Alice Lake]] at 11:30 AM

- Staff meeting at 10:00 AM✅ Viola! We started with disparate calendar and contact data and ended up with information we can use in a helpful location!

Are you interested?

I want to give you a nod of appreciation for making it this far!

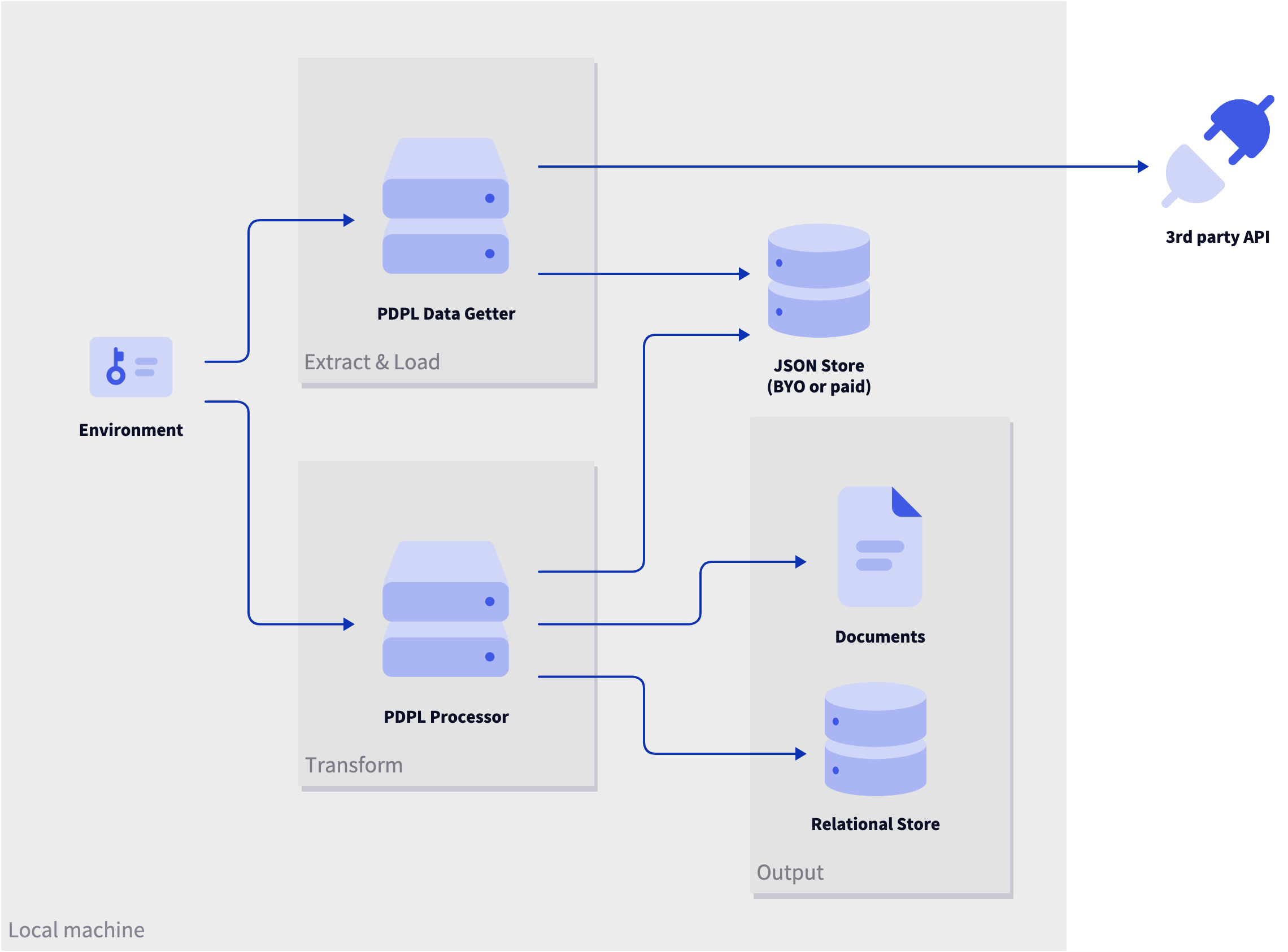

This post originally started as an explanation of a concept I wanted to explore but, as I worked on the proof of concept more, it felt like it should, and could, be working before the post saw the light of day. So, over the last few months, I wrote the two main components, the Data Getter and the Processor. I added contracts for Google Calendar and iCloud Contacts importing and an output processor for Obsidian daily notes.

Right now, PDPL is a more simplified version of the one described above:

There is a long way to go before PDPL can do everything I described above but you can try it out using the tutorial below. This runs through how to set up the Data getter and generate a CSV of the output.

Whether you are someone who has written something like this before or wishes that this kind of thing existed, I would love to hear from you. If you want to hear updates when I have them, sign up on Substack and I'll send updates on how the system is coming along and new releases. If you're looking for a more substantial contribution:

- Give this system a try and let me know if you have any problems. I'd be happy to pair with you to get it working or write any API contracts or output handers that would help get you started.

- Reach out via Discord, Twitter/X, LinkedIn, or Hacker News and let me know what you think about the idea or the implementation or any questions you have about getting started.

- If you have specific requests or feedback about specific components or technical choices, post an issue on GitHub or contribute to one of the discussions there.

I'm specifically interested to hear feedback about the declarative processing, specific use cases, pitfalls from your experience, or "product" feedback from potential users, especially folks who would use something like this but do not have the ability (or desire) to build it themselves.

< References >

- PDPL CLI on GitHub and npm

- File over app philosophy

- A human programming interface (HPI)

- A personal data search engine

- Building a memex

- MotherDuck's small data manifesto

< Take Action >

Comment via:

Email › GitHub › Hacker News ›

Subscribe via:

< Read More >

Tags

Newer

Aug 07, 2024

My Values for Technical Leadership

My professional values as an engineer, architect, and technical leader.

Older

Apr 08, 2024

Building a CLI from scratch with TypeScript and oclif

I'm building a pair of CLI programs in TypeScript and decided to use oclif for flag parsing and releasing. I needed something more than the getting started doucmentation they had so I wrote it myself.